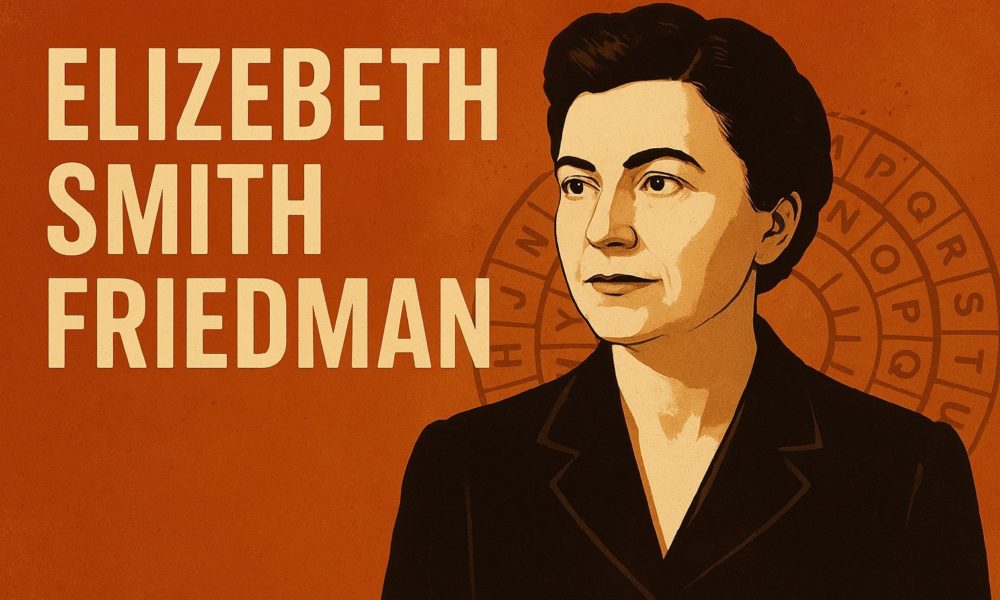

Breaking Codes, Changing History: The Story of Elizebeth Friedman

How America’s First Female Codebreaker Outwitted Criminals, Spies, and History

Countless women throughout history have been overshadowed by gender biases, their achievements attributed to men or overlooked entirely. Elizebeth Smith Friedman (1892-1980) is one such extraordinary figure whose groundbreaking work in cryptology remained hidden for decades.

Born in Indiana, Illinois (USA), Friedman displayed an early passion for language and literature, particularly Shakespeare. She graduated from college in 1915 and started her career at the Newberry Research Library in Chicago. There, her remarkable linguistic talents caught the attention of George Fabyan, the wealthy founder of Riverbank Laboratories in Geneva, Illinois. Riverbank would become one of the first cryptography centers in the United States.

At Riverbank, Friedman’s aptitude for pattern recognition and her uncanny ability to make accurate cryptographic guesses set her apart. Historian Amy Butler Greenfield notes, “She was extraordinarily good at recognizing patterns, and she would make what looked like guesses that turned out to be right.” It was here, in 1917, that Elizebeth met her future husband, William Friedman, introducing him to the world of cryptanalysis. Though William would later become celebrated as the “godfather of the National Security Agency,” it was Elizebeth who was the first female cryptanalyst in America, and she effectively directed the US government’s codebreaking team during World War I, despite official titles recognizing only her husband.

In 1921, the Friedmans moved to Washington, DC, to work for the War Department. Soon after, Elizebeth became a cryptanalyst for the Navy and, later, led the Coast Guard’s cryptanalysis unit. She played a pivotal role in decoding the encrypted communications of Prohibition-era smuggling rings. Over three years, she personally deciphered over 12,000 messages, leading to 650 criminal prosecutions and the dismantling of numerous illegal liquor operations along the US coasts.

Elizebeth’s expertise extended into World War II. When the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) struggled to monitor Nazi spy communications in South America, she and her team at the Coast Guard took on the challenge. They intercepted and decrypted messages, uncovering the identity of the spy network’s leader, Johannes Siegfried Becker. By breaking these codes, she effectively disrupted Nazi espionage operations, preventing their plans from reaching US soil.

Despite her decisive work, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover falsely claimed credit, illustrating the systemic barriers Friedman faced as a woman in her field.

After retiring, the Friedmans devoted themselves to scholarship, co-authoring The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined. Their work debunked the long-standing theory that Francis Bacon authored Shakespeare’s plays, earning recognition from the Folger Shakespeare Library and the American Shakespeare Theater and Academy.

Recognition for Elizebeth’s contributions has grown posthumously. In 1980, the year of her death, the declassification of World War II records finally acknowledged her role. In 2002, the National Security Agency dedicated the William and Elizebeth Friedman Building in their honor. Further tributes include a 2019 Senate Resolution commemorating her life and legacy, and the 2020 christening of a Coast Guard ship bearing her name.

Elizebeth Friedman’s story is a powerful reminder of resilience, brilliance, and the importance of giving credit where it is due. Her legacy continues to inspire cryptologists, historians, and advocates for women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), proving that talent and determination can leave an indelible mark on history.