Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell: A Life of Outstanding Service to Humanity

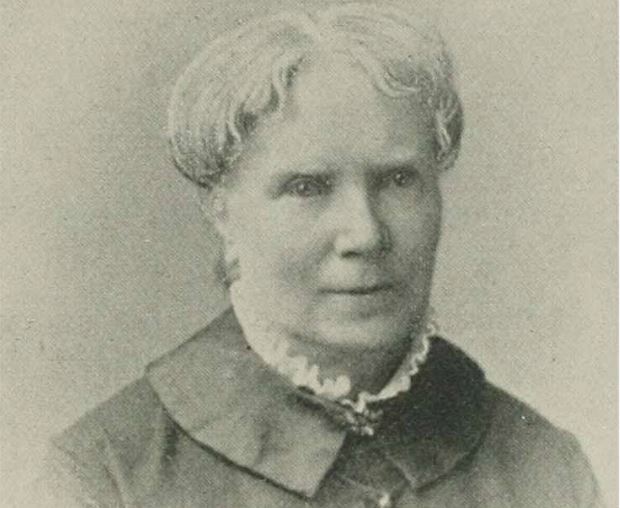

History is full of examples of prejudices based on the inexplicable “rationale” that some people are born “lesser” (in other words, non-white, non-male, of different beliefs, lifestyles, or nationality) but one woman, Elizabeth Blackwell, exemplifies the juxtaposition of such limited mindsets with those able to see past others’ limitations.

Born in England in 1821, Elizabeth Blackwell grew up in the traditional home of a successful sugar producer. When a fire destroyed her father’s refinery, the family moved to New York in 1832. Blackwell’s father died when she was 17, so she and her sisters started a home school to support the family: the Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies. But inspired by other ideas, Blackwell focused her attention on medicine when a friend fell ill and expressed the belief that a woman doctor might have offered more beneficial treatment. Although no female doctors existed – society considered the idea ridiculous in the 1800s – Blackwell was not to be deterred.

In 1847, after applying to 30 medical institutions, Blackwell became the first woman accepted into a medical school in the United States, at New York’s Geneva Medical College. Her acceptance, though, was meant only “as a joke by the men,” to make the point that women belonged at home or in “appropriate” work. According to one account, her “professors forced her to sit separately at lectures and often excluded her from labs; [and] local townspeople shunned her as a ‘bad’ woman for defying gender role.”

At this period of time, the medical profession believed only men should be treating patients, even women seeking advice or treatment in the area of “gynecology” (a term from the Greek meaning “the study of women”). Yet Blackwell proved them wrong.

In 1849, she became the first woman to receive a Doctorate of Medicine from an American medical school, surpassing the male students to graduate first in her class. As she herself put it, “The idea of winning a doctor’s degree gradually assumed the aspect of a great moral struggle, and the moral fight possessed immense attraction for me.”

Blackwell was just getting started on a list of goals, projects, and initiatives that would overshadow most male doctors of the 19th century.

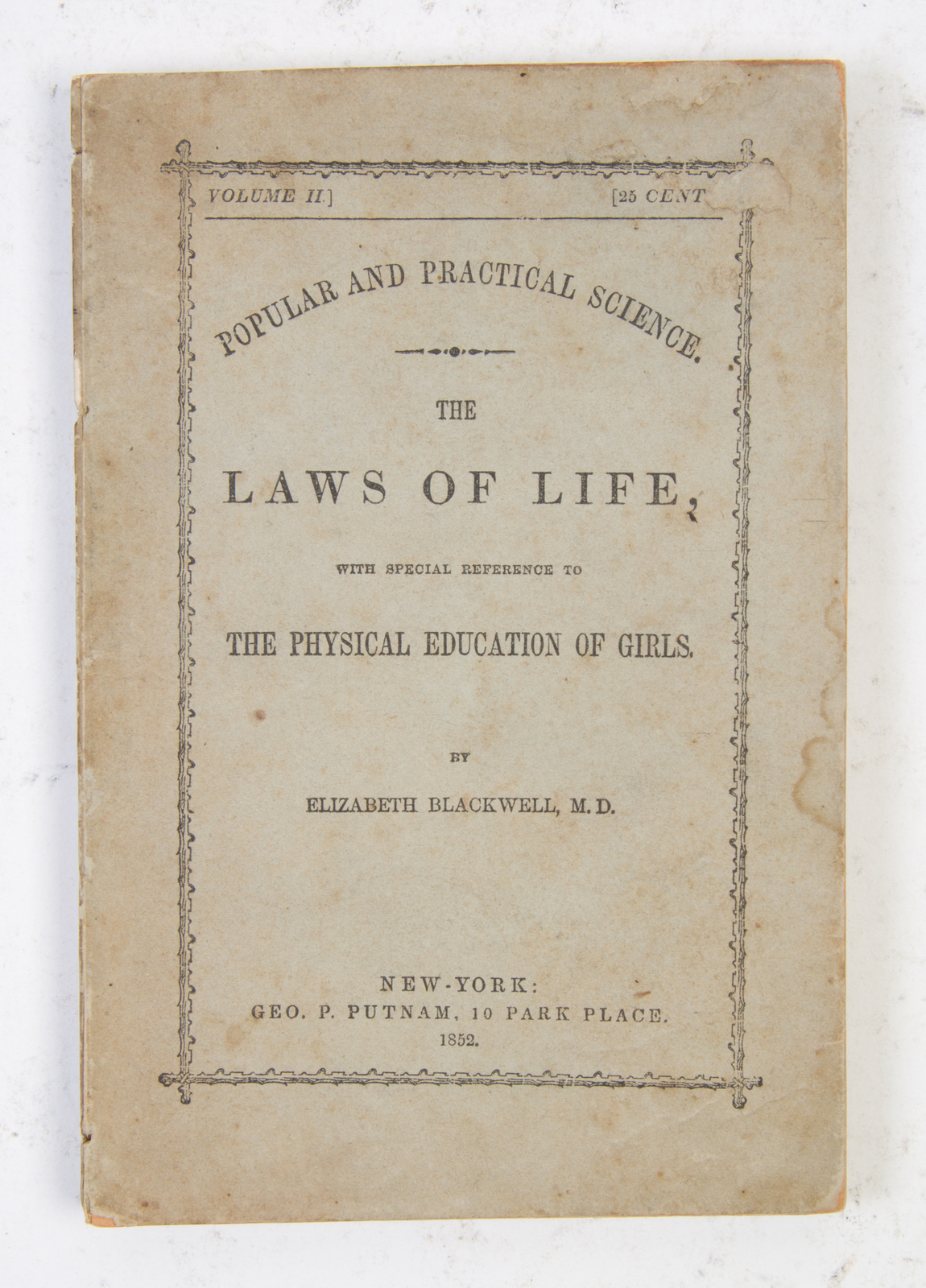

She began her medical career in 1850, working in clinics in London and studying midwifery at La Maternité in Paris, where she lost an eye in an accident, ending her aspirations of becoming a surgeon. Undaunted, she returned to New York City where she opened a small clinic with Quaker friends to treat poor women while publishing a series of lectures entitled The Laws of Life, with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls. According to Famous Scientists, in 1857 she founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children with her sister Emily Blackwell, who had also become a doctor. She began a year-long lecture tour of the UK in 1858, encouraging women to pursue careers in medicine, before becoming the first woman to qualify for the British Medical Register. This allowed her to practice in the UK, before returning to New York in 1859 to continue working at the infirmary.With the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War in 1861, Blackwell selected and trained nurses for the Union (North) side. She actively advocated for sanitary care after witnessing male doctors failing to wash between treating wounded patients, resulting in infectious outbreaks. After the war, she continued to pressure the medical establishment to accept women into the healthcare profession and, in 1868, opened the Woman’s Medical College in New York City in consultation with British nurse and reformer Florence Nightingale. It operated for three decades and was absorbed by Cornell University Medical School in 1899 when the university finally began accepting women students.

But Blackwell’s work didn’t stop there. She returned to England where she created the National Health Society in 1871 to advance knowledge on hygiene and healthy lifestyles, and then helped launch the London School of Medicine for Women, where in 1875 she accepted the Chair of Gynecology. A year later, however, her own ill-health obliged her to retire from both lecturing and practicing medicine.

Blackwell published numerous written works, including her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women (1895); “Medicine and Morality” in The Modern Review: A Quarterly Magazine (1881); Purchase of Women: the Great Economic Blunder (1887); and The Influence of Women in the Profession of Medicine (1889).

A fall in her 86th year left Blackwell physically and mentally disabled, and she died of a stroke at the age of 89 in 1910.

Amid tireless efforts to improve health care, her lingering influence includes an emphasis on preventive care, proper hygiene, and public sanitation, and the promotion of women’s education in medicine. Her accomplishments are celebrated annually through the Elizabeth Blackwell Award, conferred by Hobart and William Smith Colleges “to a woman whose life exemplifies outstanding service to humanity.”